“Water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink”, a line from “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge best captures my thoughts on this subject.

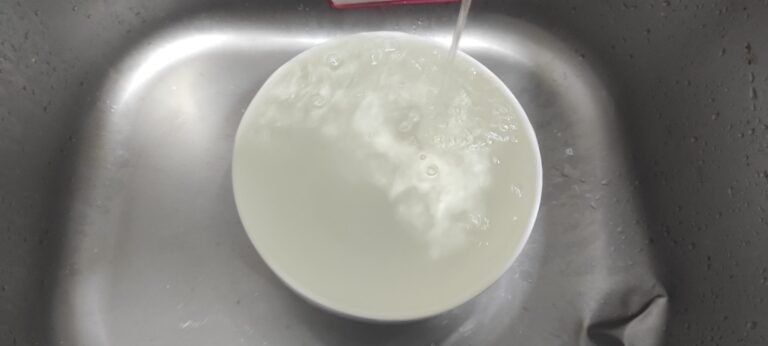

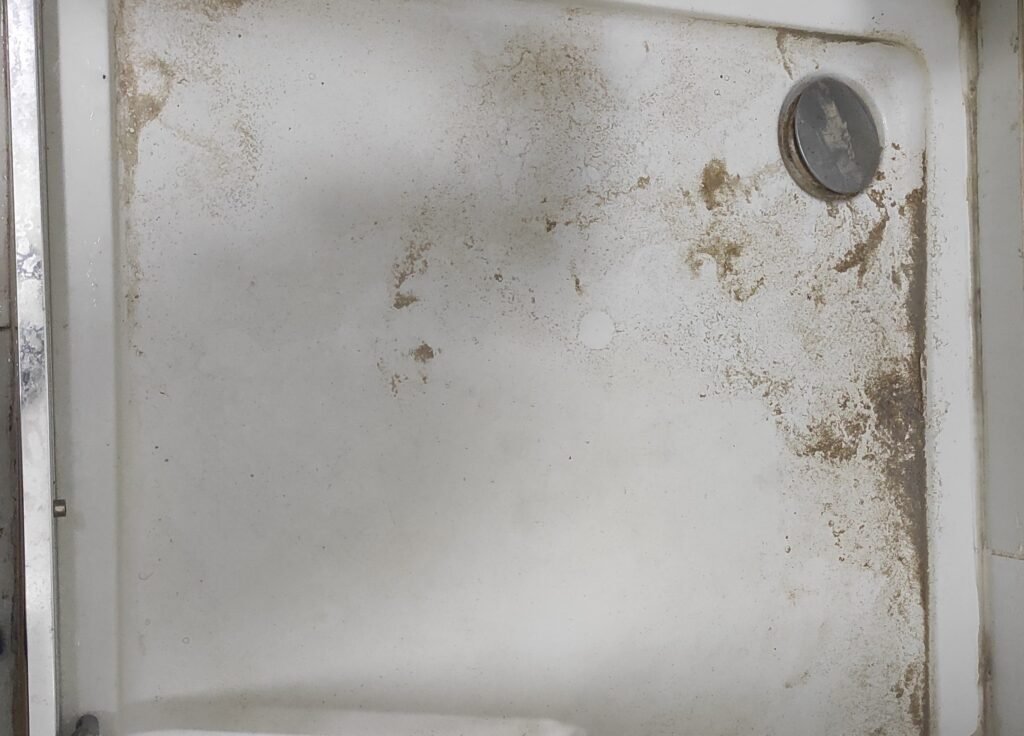

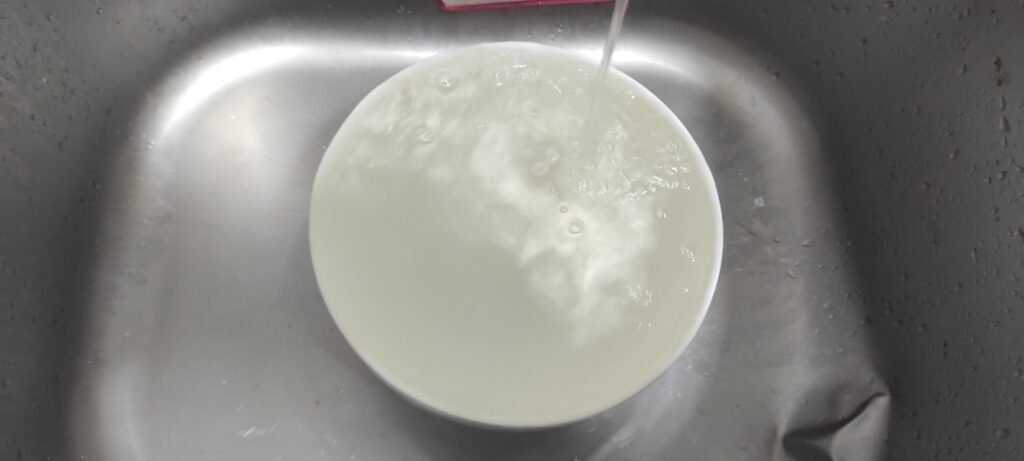

In the last 7 months, I have visited Lagos a number of times, and on those occasions, I had reasons to spend some days and sometimes weeks on the Lekki axis of Lagos. Having lived on the mainland all through the period I was permanently resident in Lagos, I couldn’t imagine the enormity of the dirty water situation in Lekki, and perhaps its environs. The pictures herein may tell a better story.

One of the things that baffled me the most was that most residents I spoke to about the poor quality of water in Lekki didn’t seem to give a hoot about it. I couldn’t miss the palpable unspoken response from most residents – clean water in Lekki? Who cares? Sort yourself out.

My nearly two weeks of experience in a short-let apartment in Lekki phase 1 got me thinking. Why would a rich neighbourhood like Lekki get used to consuming dirty water? I recall asking myself, isn’t Lekki just an expensive ghetto, especially when compared with other expensive neighbourhoods in other climes? I think, for many residents in Lekki, something as simple as owning white cotton underwear is such a luxury, given the ‘brown water’ prevalently available in most homes.

What are the economic implications of the dirty water situation?

Certainly, because we do not have the habit of measuring important things as precisely as we should, other times it could be a matter of lack of interest in and funding for gathering relevant data to measure, in Nigeria, there is certainly no reliable data to accurately estimate the economic implications of the dirty water situation in Lekki and its environ.

However, there are a few ways to attempt a hypothetical estimation of the implications: first, it will be necessary to imagine the health challenges that are commonly associated with dirty water including typhoid fever, cholera, hepatitis, kidney failure, skin infection, etc. And attempt to find out how many people around you are regularly suffering from any of these illnesses, if they ever diagnose what exactly they suffer from when they fall ill.

According to a statement on healingwaters.org, “with unclean and contaminated water, more toxins enter the body than those that leave it, creating a harmful environment for bacteria and illness to spread.”

Photo credit: Jonas KIM

A report by World Health Organisation states that “some 829 000 people are estimated to die each year from diarrhoea as a result of unsafe drinking-water, sanitation and hand hygiene. Yet diarrhoea is largely preventable, and the deaths of 297 000 children aged under 5 years could be avoided each year if these risk factors were addressed”.

The aforementioned dirty-water-associated illnesses combined with their general negative impact on average individual’s productivity should be of collective interest to and a source of worry for any community.

Second, is to imagine the level of investments some families and organisations make individually to purify water they mostly source underground. This drains part of their resources that could have been invested in other important areas. Just think about the resources that could be saved if there’s an efficient centralized water purification and distribution system in Lekki alone.

Whose responsibility is it to solve the dirty water situation in parts of Lagos?

Water is a basic necessity in any society. On that premise, the primary responsibility rests on the government.

However, in one of my previously published articles – “Academia-community partnership in Nigeria: Can we change the narrative?” I tried to make a case for higher education institutions’ responsibility for improving the economic vitality of their host communities/cities.

In reference to the dirty water situation in Lekki, I similarly feel that higher education institutions in Lagos should feel a measure of responsibility in finding a lasting solution to the water crisis in Lagos, perhaps beginning with the peculiar case in Lekki and its environs.

You may want to argue that this expectation from the public universities in Lagos is misplaced considering that that public universities in Nigeria have not been able to resolve their own internal issues with the government let alone focus on external issues.

My thought is not for the University of Lagos and/or Lagos State University to focus on solving the water problems of Lagos from an infrastructure perspective but to at least focus on providing well-researched solutions and bring deserved attention to an ignorantly neglected issue in Lagos.

For instance, knowing that clean water is one of South Africa’s major challenges, the University of Cape Town in South Africa through The Future Water Institute has been conducting “engaged research on water sensitive approaches that sustain society’s current and future water needs” with the slogan #slowtheflow. This for me is an example to emulate.

However, note that no higher education institution in Nigeria (or anywhere in the world) should pretend/seek to be world class and yet not be able to focus on solving big issues in its host community/city.

In fact, being world class is being local. Notably, what world class institutions do is to keep aggregating global knowledge from a diverse students and faculty to solve local issues, at a global scale if you like. Often, whatever is regarded as a global issue is first and foremost a local issue to a community.

For me, the hitherto neglected dirty water challenge in Lekki should be a multidisciplinary assignment for the likes of the University of Lagos and Lagos State University. And a responsible government should be partnering with its institutions of higher learning to solve society’s pressing needs.

Isn’t this a practical, responsible way to build sustainable communities and world class institutions? But, who cares?